We always hear about the importance of starting early to save for retirement. This yields several questions:

- Why start early? Why can’t you just focus on your bills now and “catch up” later when you are earning more money?

- What does “save” mean? Does this mean putting money in a savings account?

- What is “retirement”? Is retirement something you do at Age 65? If I love working, does that mean I don’t need to save?

The truth is that both “saving” and “retirement” are misnomers. The key is to invest for financial independence. This means having enough assets to cover your living expenses without having to work again. This might include having enough money to support your significant other and family, too. Whether you “retire” in the traditional sense or not is your choice.

Why start early? There are two big reasons:

- Compounding returns

- Avoiding taxes

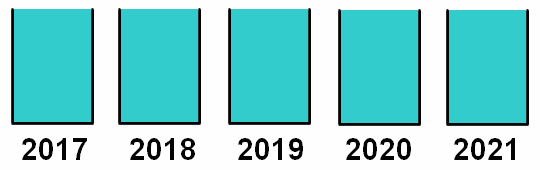

Over several decades or longer, the stock market is the best place to put your money. Here is a graph of the S&P 500 index over the past 66 years, which includes 500 of the most valuable companies in the world:

Although you can enter the investment curve at any point, the earlier you start, the greater your returns will be. Even if you happened to invest the bulk of your money at the worst possible timing (immediately before crashes), over 30 or 40 years you would still have returns somewhere around 9% per year even adjusting for inflation. This means in 40 years, initial investments will be worth about 31 times more in inflation-adjusted dollars, even using historical worst-case scenarios. For example, $18,500 put in a 401(k) now will probably be worth at least $1.2 million in 2058 in nominal dollars, or $575,000 in inflation-adjusted dollars. Of course, past market performance is not necessarily sustainable, but it is very much a sure bet that you will come out far ahead.

The second big reason to start investing early is to avoid income taxes. There are several types of accounts the IRS has given tax-advantaged status, meaning that you either don’t pay income tax on the money when it goes in (“traditional,” pre-tax retirement accounts), or you don’t pay income tax when the money comes out (Roth, post-tax retirement accounts). Health savings accounts are even better—you don’t pay income tax at all (i.e., you can deduct your contribution on your tax return and not pay income tax when you cash out to pay medical bills). Such accounts may be especially valuable in states with state and local income taxes:

- 401(k) or 403(b) accounts – $18,500 per year

- Individual retirement accounts (IRAs) – $5,500 per year

- Health savings accounts (HSAs) – $3,400 (individual) or $6,750 (family) per year

- College savings accounts (529 plans) – Varies

A key characteristic of tax-advantaged accounts is annual contribution limits. This is why starting early is so important. Ideally, you have high-interest credit card debt paid off and a few months expenses saved (an “emergency fund”). Then, you concentrate on putting money into tax-advantaged accounts to avoid income tax now or capital gains tax later. These accounts are just wrappers for other investments. Your employer probably uses Fidelity for 401(k) contributions, so you would contribute part of your paycheck to a broad, low-fee fund like their S&P 500 index fund. You have to set up an IRA separately on your own, which you could do through Fidelity or Vanguard, putting your money in the same passive index fund or a similar one. Ideally, your annual contribution limits would look like this:

Unfortunately, past trends will continue. Far more Americans’ annual contributions will look like this in the coming years:

You do not want to follow the herd. Many people feel it’s too dangerous to put money away from retirement when they might need it sooner. However, statistically, you will almost certainly live to Age 59.5 or older and, at that time, money will still be useful. Moreover, retirement accounts are an important safety net because even if you go bankrupt, your creditors usually can’t touch them. Further, although other accounts have penalties, contributions to a Roth IRA can actually be withdrawn without penalty, and this type of account is especially advantageous in youth when you are earning less and consequently are in a lower tax bracket.

In fact, you can’t even make tax-advantaged contributions to an IRA if your income is over $133,000 per year (single) or $196,000 (married), which means if you wait until the prime of your career to invest for financial independence (save for retirement), you may have missed this boat entirely! Of course, 401(k)s are still an option, but contributing to both is even better. Likewise with HSAs, you can’t contribute at all if your health insurance deductible is under $1,350 (single) or $2,700 (family), which means many people in the prime of their careers with excellent employer-sponsored health insurance coverage are ineligible, although they could have contributed in their younger years. Of course, HSAs have only been in the tax code since 2003, 401(k)s since 1978, Roth 401(k)s since 2006, and IRAs since 1974.

Tax-advantaged accounts are a modern American phenomenon ostensibly intended to help the working and middle classes save for retirement. In fact, they usually benefit two groups of people:

- Rich people who shouldn’t be helped, but are personally knowledgeable or have financial planners help them

- Non-rich people who learn about them due to a peculiar interest in personal finance not shared by the majority of Americans

People in Group 2 did not birth their way into riches, but often end up in Group 1 later in life. Although wealth comes with headaches, it comes with freedom and flexibility too. A critical step toward wealth is to investigate and begin using tax-advantaged accounts and passive stock investing sooner rather than later. “Catching up” later might require working 10 times harder to earn 10 times more money in future decades than if you start now. Remember that the bucket analogy applies to income too—higher amounts of income earned in any particular bucket (year) are subjected to higher income tax brackets. As Andy Hart is fond of saying, you invest now “so your children can dance.”

Armed with knowledge of the two big reasons to start investing for retirement now—compounding returns and tax avoidance—your next step should be to eliminate any excuses from you or your significant other’s dialog, such as:

- I’m living for today!

- I can’t invest for retirement

- The market looks too risky now (remember, you can move money between funds in your 401[k] and IRA—so you could start out with bonds or money market accounts before dipping your toes into stocks later)

- Everyone else is doing worse than me!

- I probably won’t live that long

- The government will sort it out

- I’m just focused on getting by

- I’ll save for retirement once I get that big promotion

- I need to provide for my children first

- BitCoin is hot right now

- My [financial adviser or stockbroker] is taking care of everything!

- By the time I’m old, the United States will have collapsed and we will all be bartering

Next, you need to get serious about your finances to position yourself to start investing via tax-advantaged accounts now or in the not-too-distant future. This is easier said than done, but still much easier than starting at some undefined future point in time.

The ideas presented here should not be taken as financial, investing, tax, or legal advice. Richard Thripp is not a financial adviser. Reading an article written by a stranger on the Internet does not establish an advisory relationship nor fiduciary responsibility.

Three pingbacks